Sterling fell 0.64% to $1.145 on Wednesday afternoon – a level not seen in 37 years.

The Bank of England said a weaker outlook for the UK economy as well as a stronger dollar were putting pressure on sterling.

Governor Andrew Bailey also warned that little could be done to stop the UK falling into a recession this year as the war in Ukraine continued.

He added that it would “overwhelmingly be caused by the actions of Russia and the impact on energy prices”.

The Bank expects the economy to shrink in the last three months of 2022 and keep shrinking until the end of 2023.

The warning comes ahead of a government plan to limit a sharp rise in energy bills.

Currently, a typical household’s gas and electricity bill is due to rise from £1,971 to £3,549 in October.

Energy prices climbed sharply when lockdown was lifted and the economy started to return to normal. They have increased further as Russia sharply cut its gas supplies to Europe.

It has pushed up the price of gas across the continent, including in the UK, having a huge knock-on effect on consumers.

Speaking in front of the Treasury Select Committee on Wednesday, Mr Bailey said “sadly” a recession remained the most likely outcome in the UK.

When asked by MPs if there was much that the central bank could do to stop it, he said: “Insofar as the war is having this huge effect, the answer to that would be no.”

The Bank predicted a UK recession last month as it raised interest rates by the highest margin in 27 years in a bid to keep soaring prices under control.

Higher interest rates can make borrowing more expensive, meaning people have less money to spend and prices will stop rising as quickly. But there is a limit as to how effective UK rate rises can be when inflation is caused by global issues.

Defending its recent moves, Mr Bailey added: “The person going to put the UK in recession is Vladimir Putin, not the MPC [Monetary Policy Committee].”

He said the Bank would take the new prime minister’s energy plan announcement “into account” when deciding on interest rates next week.

During her campaign, Ms Truss hit out at the Bank of England, accusing it of being slow to react to rising prices and protect vulnerable households.

But on Wednesday, the new Chancellor Kwasi Kwarteng reiterated his “full support for the independent Bank of England and their mission to control inflation, which is central to tackling cost of living challenges”.

He also said he and Mr Bailey would meet twice a week from now on to discuss the cost-of-living crisis.

Inflation could ease

Other economists also expect the UK to fall into a recession despite Ms Truss’s energy support plan – albeit a shorter and less severe one.

But some suggested on Wednesday that plans to cap energy bills could mean that increases in the cost of living will peak earlier and be “significantly lower” than previously forecast.

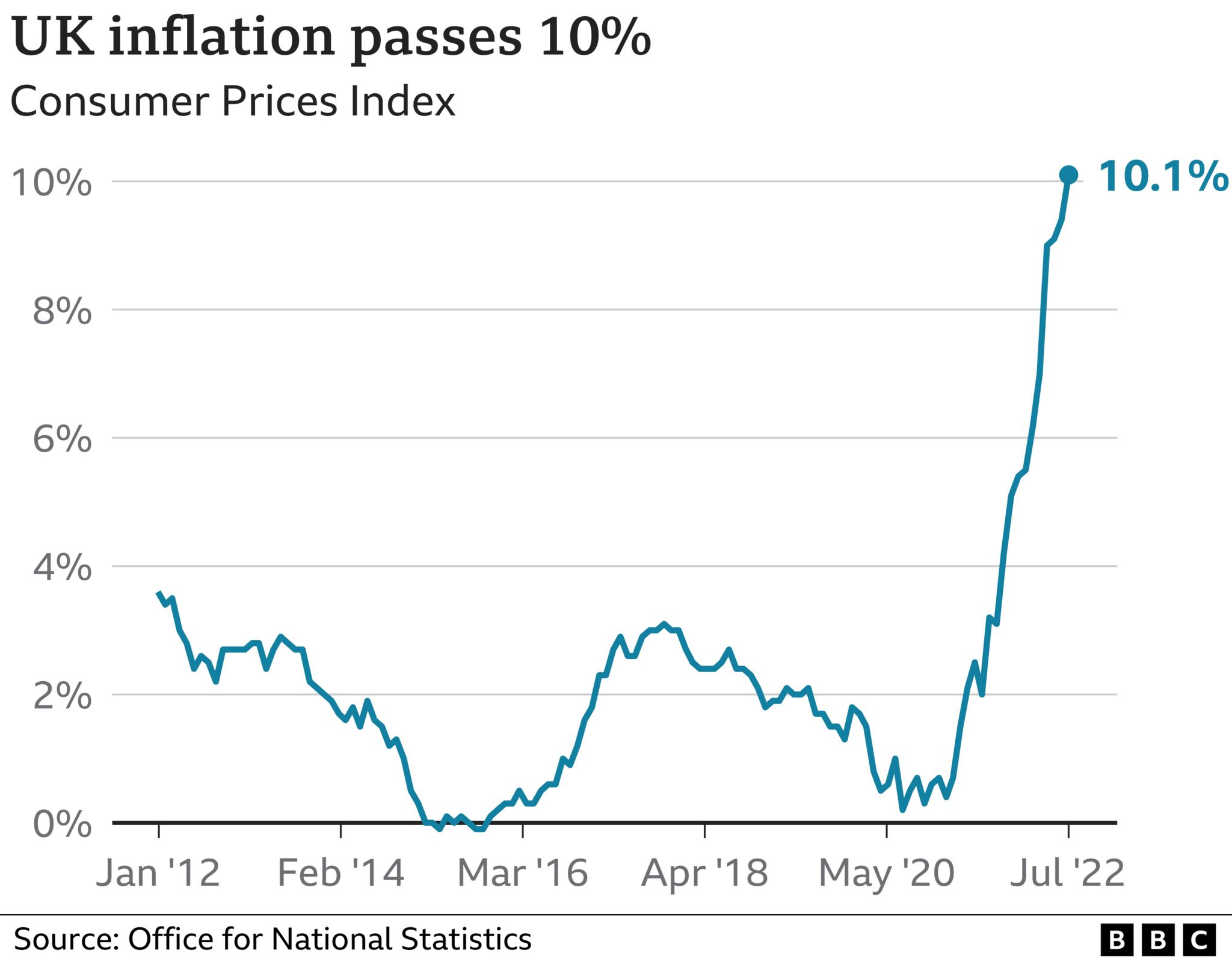

The cost of living is rising at its fastest rate in 40 years, at 10.1%, with food, fuel and energy prices all up.

Investment bank Goldman Sachs said a cap on bills for households could see inflation, which tracks how the cost of living changes over time, peak at 10.8% in October, rather than the 14.8% it forecast before. It then expects inflation to slow to 2.4% by December 2023.

Deutsche Bank, HSBC and the Bank of England’s own chief economist, Huw Pill, also believe the plan could slow price rises.

But there is uncertainty around what exactly the plan will look like and what would happen once any cap is lifted.

Mr Pill also said it was too soon to say how it might affect interest rates, which have gone up for the last six months in a row as the Bank tries to calm prices.

Others say that capping energy prices at their current level would still leave many people struggling.

According to the Office for National Statistics, four in 10 adults who pay energy bills are already finding it “very or somewhat difficult to afford them”.

And the End Fuel Poverty Coalition charity estimates that if the energy price cap is frozen at £2,500 this October, 6.9 million UK households will still be in fuel poverty this winter – up from 4.6 million last winter.

There are also concerns about the cost of Ms Truss’s plan, with research firm Capital Economics describing the support package as an “effective but expensive sticking plaster”.

Many expect the government to borrow at least £100bn, adding to the UK’s already-high debt pile. This would come as Ms Truss attempts to push through a promised £30bn of tax cuts.

On Wednesday, the chancellor said higher borrowing will be “necessary” in the short term to help people with bills.

Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, told the BBC’s Today programme: “The big question here is: ‘Is it going to be £100bn? What is the exit strategy from supporting bills?’

“My guess is it might end up being an awful lot more than that unless we react quite quickly to make it a better [energy] system,” he said, adding that the plan would benefit affluent people more than the less well off.

On the other side of the House of Commons just before the PMQs battle, was perhaps the more important Commons appearance. Governor Andrew Bailey and his team, confirming that there was not much they can do to stop a recession, blaming it on the Kremlin, and acknowledging that the UK is facing an historically unprecedented energy shock. It is heading to be three or four times worse for households than the hit to incomes in the 1970s’ oil shock.

At the same time the Bank welcomed the end of the summer uncertainty over energy bills, and anticipate that it will be big enough to prevent inflation spiralling higher. However Governor Bailey also acknowledged there were specific UK factors driving jittery markets, in addition to the strong dollar, especially the UK’s extra reliance on gas. As Chief Economist Huw Pill put it, that dependence is not going to change quickly, so the only real question is “who covers that cost?”. With sterling falling again today, to a 37 year low against the dollar, there are concerns in the markets that the PM and Chancellor will hope to contain tomorrow.